I

watched End of Days recently—a movie I haven’t seen since my salad days of

eighth-grade. While I didn’t remember much from my initial viewing of the film,

I remembered the basic premise and, more importantly, why it appealed to my

dark and depraved eighth grade mind: it’s about the devil.

For

some reason, movies, books (but not music, so much) about the devil have

appealed to me because, growing up in a bible-thumping red state, the devil is

the one thing no one talks about…along with all the other things that get

equated with the devil in a red state: rock music (excluding anything written before

grunge and after black people ceded the genre to dorky white guys doing

piss-poor imitations of black people), homosexuality, and…anything else not

promoted on a network that screams “socialism” and end-of-times prophecy at

people.

But,

the purpose of this article is not political. I instead want to focus on the

very thing that attracted me to movies like End of Days, the Exorcist, the

Omen, et. al, when I was but a mouth-breathing 14 year-old—and how I always

seem to be disappointed by the movie-version of Lucifer compared to the more

badass version of Lucifer in my head (not that I spend my days fantasizing

about the devil… I just have a preconceived notion of Lucifer—who, if you’re

going to use as a character in your movie, should measure up to his status as the greatest supernatural evil ever--that

is rarely matched by the Hollywood version). More to the point: these are the

things that irritate me about devil-movies—the four unspoken but universal

rules that all devil-movies seem to follow.

1. The

Vulgar Display of Power Principle

In

End of Days, Gabriel Byrne’s Dark Prince can do just about anything he wants.

He can kiss a man’s wife in a crowded restaurant (and feel her up at the same time!), while the man watches on—silenced

by the fierce death-stare of Byrne. He can then blow up that restaurant in

classic action-movie fashion by walking away and not looking back at the explosion—which in this case, kind of makes sense: why would the devil wan to

look back at some boring old building that’s on fire and gloat over his work

when he lives in an eternal house of flames? He can also make heads explode on

command. But one thing he can’t do is kill Arnold Schwarzenegger. Well, he

could. But the devil, while maybe not all-knowing, at least knows that killing

Arnold Schwarzenegger would mean a shorter film—and to the audience, that means

less stuff “gettin’ blowed-up,” less Arnold-mangled English, and less weird,

mom-and-daughter-plus-Satan incest sex scenes. So, at least we can thank Satan

for that.

"Thanks, Satan!"

But

this begs the question: if Satan can do all this awesome stuff at will, why can’t

he do the very thing he needs to do to get his way? In this case, killing

Arnold would mean he gets to bang that chick from Empire Records, thus impregnating

her with Rosemary’s proverbial baby and setting up the “end of days.” All he

has to do is kill Arnold—which shouldn’t be hard. Sure, the guy is stacked and

he could probably fist-butcher the skull of any human like he mouth-butchers

the English language, but…come on: You’re Satan! You make people’s faces

explode and blow up buildings for no reason. And now you have a reason to do

these evil things--because some gap-toothed Austrian is cock-blocking you from

realizing biblical prophecy. What gives, Lucy?

What “gives” is the Vulgar Display of Power Principle—first addressed in the Exorcist, likely as a way to close up the one major plot-hole in all movies about the devil. In the scene, Father Damien is talking to Regan—a twelve year-old possessed by the devil. She is strapped to a bed, with cuts all over her face and green ooze leaking out of every recognized—and some new—face orifice—kind of like what you’d imagine to be the aftermath of a blind man trying to eat split-pea soup with a pocket knife. After Regan professes to be the devil, Father Damien asks her: “If you’re the devil. why can’t you make those straps disappear?” To which Regan/Satan retorts: “Much too vulgar a display of power.”

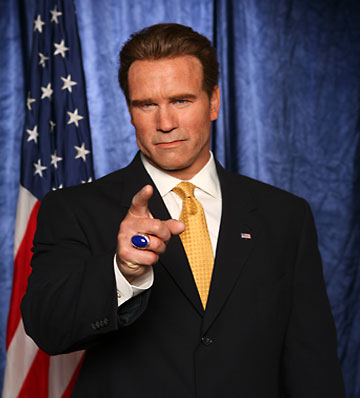

Arnold: Cock-Blocking Democrats and Satan Since 1999.

What “gives” is the Vulgar Display of Power Principle—first addressed in the Exorcist, likely as a way to close up the one major plot-hole in all movies about the devil. In the scene, Father Damien is talking to Regan—a twelve year-old possessed by the devil. She is strapped to a bed, with cuts all over her face and green ooze leaking out of every recognized—and some new—face orifice—kind of like what you’d imagine to be the aftermath of a blind man trying to eat split-pea soup with a pocket knife. After Regan professes to be the devil, Father Damien asks her: “If you’re the devil. why can’t you make those straps disappear?” To which Regan/Satan retorts: “Much too vulgar a display of power.”

True,

Satan can do some nether-worldly shit, but his one (self-imposed, I guess?)

condition is that he has to be classy about it. It’s ok to do evil, but to do

evil when expected to do evil is just pompous and in bad taste. Because if there's one thing we know about Satan, he's very conscious of general etiquette and not being "too vulgar." A little vulgar. Sure. But there's a line, here, and Satan is very careful not to cross it--lest people think he's an asshole.

It’s the same rule that applies to superheroes: they’re only allowed so much super-natural awesomeness. Superman can fly. The Hulk can…get real angry and bash and bang and break things. But too much awesomeness and they’re just being assholes. Well, that and there wouldn’t be a “story” if they could easily avoid the conflicts they find themselves in.

"I wonder if I wasn't a tad too show-y when I blew that restaurant up full of innocent civilians. I don't want anyone to get the wrong idea."

2.

The

Devil Shall Be Played By the Least Devilish-looking Actor Possible

Before

the CGI boom, actors had to play parts that can now be rendered in unbelievable

CGI. And when I say unbelievable, I don’t mean unbelievable because it’s so

good. I mean: unbelievable in the sense that you can’t believe the egregiously

bad computer-generated crappy monsters you’re expected to believe exist in the same

reality as…things that are real.

Looking at YOU, Joss Whedon!

But

I digress. In a lot of movies about the devil, the King of Hell (that's one of his pseudonym's, right?) is given a

face. In End of Days, he was played by Gabriel Byrne—whose credits include

Miller’s Crossing and…well, other stuff, I’m sure. In the Devil’s Advocate, the

devil is played by Al Pacino. In the Exorcist, the devil possesses the body—and,

by extension, face—of a little Linda Blair.

But

in all these movies, there is one glaring problem: none of these people look

even remotely evil. Al Pacino could be devilish—if by “devilish” you mean “devilishly

handsome,” as my mom—and many a mom—will certainly concede. Gabriel Byrne is

another mom-ready heartthrob. And Linda Blair….Actually, Linda Blair works

because she looks (or did look, when the Exorcist was shot) like a pretty

average-looking kid and part of the creepiness comes from her being so normal

and so…possessed by Satan. It’s a terrifying contrast of extremes: ultimate

evil vs. ultimate innocence signified by Blair’s ultimate average-looking

kiddi-ness.

Pictured: Linda Blair in a rare Puberty Affects Everyone PSA from the 1970's

But

let’s say you wanted to make your own movie about Satan. Wouldn’t it make more

sense to cast a cracked-out Gary Busey—someone who already looks evil by way of

always looking batshit insane? Or (how do I put this delicately?) someone with

less mom-appeal than Byrne or Pacino? Someone whose inherent “grotesque”

features already lend themselves to the part? Steve Buscemi, perhaps? No disrespect

to Buscemi, but…come on, tell me Steve Buscemi as the devil wouldn’t be the

best thing you ever saw?

I’m

not complaining, per se. I get it: it’s interesting to see the devil characterized

as a suave dude who could probably make your mom run away with him just by

accidently making eye-contact with her (and is there anything more evil than

mom-stealing?). But it’s tired and it’s played-out. I want a devil who my mom

wouldn’t bone. A devil who makes my mom’s ovaries (did I really just type

that?) shrivel up in disgust at the sight of his ugly, devil face. And I know

Steve Buscemi is right for the part because every time my mom sees him on

television, she averts her eyes, choking back something physical—instant infertility

perhaps?-- that happens to moms when they see the opposite of Al Pacino. “Ugh,”

she says. “That guy….”

"Moms hate me....I must be evil."

3.

The

Guy We’re Supposed to Root For Shall Always Be Wrestling With His Faith

This

trope isn’t exclusively anchored to devil-movies. Signs did it. Patch Adams did

it. And it was the premise of every episode of Touched By An Angel. What

happens is this: the main character is usually a pretty devout believer in God—until

something horrible happens (more often than not: the protagonist’s family dies)

which causes the main character to abruptly turn on his heels and refute

everything he previously stood for. In Signs, Mel Gibson used to be a preacher.

Then his wife died. In the Exorcist, Father Damien is a priest. But his mom

dies. In End of Days, Arnold Schwarzenegger’s wife and daughter die. They never

address whether or not he was an atheist before this happened, but he does say

that he doesn’t believe in God now (when the film takes place) because of it.

Obviously,

losing a family member—or all of them—is pretty tragic. And it probably leads

one to question a lot of things—including their religious or non-religious

convictions. The thing that irritates me, though, is that after this happens,

the character is exposed to all forms of super-natural fucked-up-ed-ness but

still refuses to acknowledge that anything is out of the ordinary. In the

Exorcist, Father Damien watches Regan turn into a blistering mess of puke and

evil, able to move furniture at will or write cryptic messages in her stomach

while her arms are bound. And…he still doesn’t think any of it is real.

Pictured: the face of a man who is absolutely sure what he's just witnessed is all hocus-pocus.

There’s

a scene in End of Days, towards the end, where Arnold takes the girl (Satan’s

intended) to a church where he learns she will be protected—because Satan

apparently can’t enter the church. Never mind for a minute that Arnold's character doesn’t believe in God—so

why would he believe in Satan?—he’s still on-board with the whole

safe-from-Satan-in-a-Church thing. A priest then explains to Arnold why all the

strange shit that’s been happening since he got involved with this case (did I

mention Arnold is a cop in this movie?) is happening—to which Arnold retorts,

in one of the more unintentionally funny (with his trademark emphasis on the

wrong part of a sentence) lines in the movie, “cut the religious mumbo jumbo.”

I

call this: the Scully and Mulder effect. In the show the X-Files, Scully and

Mulder played opposites. Mulder was the die-hard JFK, fringe-conspiracy

fanatic who was ready, before even embarking on a case, to say aliens were the culprit.

No matter what happened: aliens. Scully, on the other hand, played off Mulder’s

childlike willingness to “believe” by playing the role of a douche-skeptic: outright refusing to believe in anything

supernatural or alien-related, despite seeing supernatural, alien-related

phenomena in the week’s previous episode, every week. So, either she was just being a turdy

contrarian or she suffered from the worst case of one-week amnesia. Something

bizarre would happen and Mulder would be all like: “Aliens, Scully. Aliens!”

And Scully was all: “That’s insane, Mulder. I know we encounter aliens in every episode—and, sure, I've seen them first-hand—but--no, just--no, that’s patently ridiculous.”

"Right. Aliens exist just like I've been wearing the same pant-suit since Season 1. Get over yourself, Mulder...."

To

be fair, the best way to create dramatic tension (the most obvious way, anyway)

is to make compelling characters who disagree with each other—or two characters

who represent two polar opposite extremes. This worked for the X-Files. Because—hey,

it’s TV. Who cares? But I expect a little more out of my devil-movies.

But

I really shouldn’t expect much from devil-movies, because…

4.

Most

Devil-Movies Suck

That’s

right, I said it. devil-movies suck. And I don’t mean they suck because they

don’t get good reviews or because they don’t look, behave or act like movies

that don’t suck. They just flat-out…suck.

Sure,

End of Days has its entertaining parts. And the Devil’s Advocate has Charlize

Theron nude. And Stigmata…had Billy Corgan do the soundtrack. But, most of the

time, these movies are just…kind of boring.

I’m

of the Quentin Tarantino school-of-thought when it comes to movies that suck.

Paraphrasing here, but: “There is no such thing as a bad movie. It’s either

entertaining or it’s not.” Unfortunately, for so many movies about the devil,

they fall into the latter category—either because of the exhausted tropes (the

crisis of faith thing, uninspired characterization of the devil as a suave dude

you’re mom would bone) or because—and I don’t know why this seems to always be

the case with horror films—the plot is too convoluted and not at all

fleshed-out in a way to hold anyone’s interest.

If you’re going to write a movie about a character who represents absolute evil, at least make it…kind of interesting. Don’t just dilly-dally with plot-points that, no matter how much you try to make them make sense (one primary reason for the convolution), don’t make sense, so you have to keep trying to explain them, just digging yourself deeper and deeper into that unholy wormhole. We know he’s the Devil. And that’s all we need to know. He’s going to do some evil.

"Mmm. Genius tastes yummy."

If you’re going to write a movie about a character who represents absolute evil, at least make it…kind of interesting. Don’t just dilly-dally with plot-points that, no matter how much you try to make them make sense (one primary reason for the convolution), don’t make sense, so you have to keep trying to explain them, just digging yourself deeper and deeper into that unholy wormhole. We know he’s the Devil. And that’s all we need to know. He’s going to do some evil.

To

quote Arnold, “cut the mumbo jumbo”—since most of it (as with End of Days)

revolves around taking biblical quotes out of context and trying to make them

make sense within the context of the film (which never really works). We get

it: the Devil has his reasons for doing evil. And I have my reasons for wanting

to see someone do evil in movies. But by taking time out to explain to me

something I already know (that the Devil is evil) is just delaying what I really came to see: the random

head-explosions and fiery boom-booms.

That

said: the Exorcist is the exception to this rule.

No comments:

Post a Comment